Updated by Zack Beauchamp on November 16, 2015

On Thursday, one day before terrorists who appear to have been linked to ISIS launched a series of devastating attacks across Paris, President Obama went on ABC and made a comment that now looks pretty bad:

What is true is that from the start, our goal has been first to contain, and we have contained them.

In the wake of Paris, it looked to many like Obama had badly overhyped his administration’s efforts against ISIS. At Saturday’s Democratic presidential debate, moderator John Dickerson asked Hillary Clinton if the quote meant that the Obama administration’s legacy will be “that it underestimated the threat from ISIS.”

Obama’s comments don’t look quite as bad in context. Rather, as PolitiFact points out, Obama was saying that ISIS’s territorial expansion in the Middle East has been contained — that, partly as a result of US actions, its march across Syria and Iraq had been halted. That’s both a much more modest claim and factually correct.

“The statement is, in the context of the interview … almost entirely correct,” Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, a senior fellow at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, told me.

But as the Paris attacks show, that in itself is hardly cause for triumphalism. And it’s not necessarily a coincidence that this attack occurred as ISIS has been losing ground in Syria and Iraq. Perversely, the world’s success in containing ISIS territorially actually makes the group more dangerous internationally, at least in the short term.

Some analysts worry that as ISIS suffers battlefield losses, it may shift more of its energy away from the battlefield and into international terror attacks like what happened in Paris.

ISIS is losing ground in Syria and Iraq

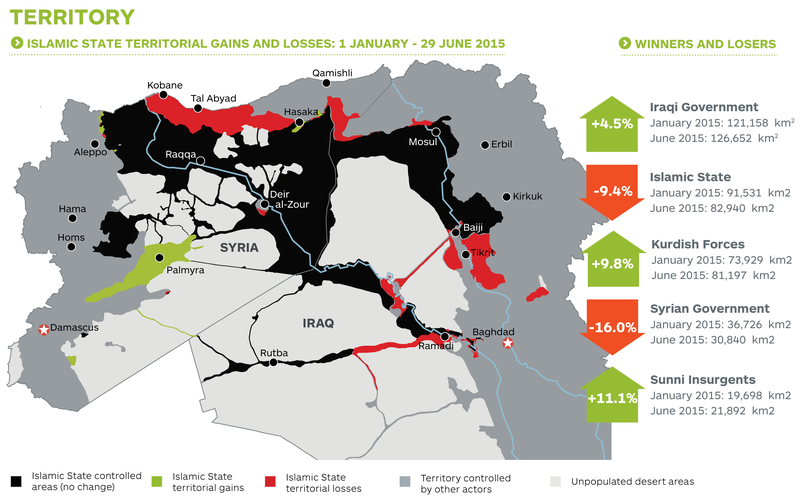

On the ground in Iraq and Syria, ISIS has in fact been stalled and in many places even turned back. According to Will McCants, the head of the Brookings Institution’s Project on US Relations With the Islamic World, ISIS “lost something like 25 percent of their territory” since its peak last summer.

By the end of June 2015, ISIS had lost nearly 10 percent of the remaining territory it held at the beginning of the year. Red areas on this map show ISIS territorial losses, and green shows gains:

(IHS Jane’s 360)

At the end of June, Kurdish fighters broke through in northern Syria, taking the strategic town of Tal Afar and advancing to within roughly 30 miles of ISIS’s de facto capital, Raqqa.

These losses have continued since.

“You look back to the past two months,” Gartenstein-Ross says, “and it’s just two month of steady losses.”

He ticks off a list of ISIS losses: Baiji district in Iraq, almost all of its presence near the Kurdish-held city Kirkuk, the outlying areas near Ramadi, and defeats in parts of Syria (like northern Aleppo). Just last week, ISIS lost the Iraqi town of Sinjar, which cuts off an important highway connecting its Iraqi and Syrian holdings.

None of these losses mean that ISIS is on the verge of collapse. Rather, they’re part of a slow but steady process of chipping away at the group’s holdings, taking advantage of its structural weaknesses — too many strong enemies, vulnerability to airpower, no real ability to hide — to put it on the path toward defeat.

“Right now — and I approve of this — we’re moving at a very deliberate rate,” Michael Knights, the Lafer fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, says. “We’re pushing forward nice and slowly, snipping off little bits of the caliphate, [and] building our confidence.”

The problem: As ISIS weakens, it could get more dangerous abroad

(As ISIS loses territory in Syria and Iraq, it poses less of a danger to the people who are far and away its primary victims: Syrians and Iraqis. Still, whether Obama meant to imply this or not, his comments sounded to many like an argument that because ISIS was being contained territorially, it was less of a danger; that the threat it posed to the US was being contained as well.

Obama’s comments were “terribly, terribly phrased — just disastrously,” Gartenstein-Ross says. “When you use the term ‘containment,’ people naturally think of it on two sort of dual tracks, terrorism and territory.”

As ISIS weakens as a state by losing territory, it may actually become more dangerous as a terrorist organization. Until Paris, ISIS didn’t really focus much effort on staging attacks on foreign targets outside of the Middle East. Some analysts worry that Paris represents the beginning of ISIS devoting more resources to staging these dramatic attacks outside its territory — perhaps in part to compensate for its territorial losses.

“We don’t yet know that there’s a trend,” Gartenstein-Ross cautions. “But I do think it’s likely that that pivot does and will exist.”

ISIS thrives on a narrative of victory. The reason it attracts so many foreign recruits, including Westerners, is that it sells itself as the prophesied Islamic caliphate: that its victories are inevitable and divinely inspired. If it’s losing territory, then it needs to sell this narrative through other means. That means claiming “victory” over the West by hitting it with terrorist attacks.

“Much of ISIS’s ideological support and recruiting strength emanates from a narrative that it is victorious,” J.M. Berger, the co-author of ISIS: A State of Terror, explains via email. The Paris attack “changes the conversation from ‘ISIS is contained’ on November 12 to ‘ISIS is rampaging uncontrollably’ on November 14.”

Moreover, ISIS may believe that terrorist attacks are its best way of striking back against — and maybe, it believes, deterring — foreign attacks. That conclusion would likely be wrong, but ISIS may still believe it. The French are part of the US-led coalition bombing ISIS in Syria and Iraq. ISIS suicide bombers have also recently hidden in a civilian part of Beirut where Hezbollah, an ISIS enemy, is strong. The group is also suspected of bombing a Russian civilian airliner in Egypt.

From ISIS’s point of view, these kinds of attacks could be a way to warn off countries that are partly responsible for its territorial defeats. The more you fight ISIS, the more of a target you become — and ISIS won’t leave you alone until you leave it alone.

“I think it has made the calculation that it can no longer pursue its expansion strategy in Syria and Iraq without changing the calculations of the enemies currently halting its expansion,” McCants says. “These attacks would be a way of inflicting costs on them.”

Gartenstein-Ross sees a similar logic at work. “If you’re experiencing territorial losses, how do you make up for that? Well, pivoting to asymmetric warfare makes a lot of sense,” he says. “You can impose a cost on countries for being part of an effort to beat you back.”

It is ISIS’s status as both terrorist group and mini state that make it so dangerous: Until ISIS is defeated more thoroughly in its Iraqi and Syrian territory, it will have substantial resources at its disposal to plan and execute international terrorist attacks.

“ISIS is a state that has millions of dollars that it can spend on these kinds of operations,” McCants says. “We’re not talking about al-Qaeda hiding out in Pakistan. We’re talking about an actual government that has money to put behind plots and has very motivated people, many of them with European passports that can carry them out.”

That suggests a kind of grim irony to the ISIS war. In military terms, the campaign to defeat ISIS is going better than most people think. But in some ways, at least in the near term, that may be making ISIS more dangerous than ever.